Biologist finds new approach to understanding the puzzle of human development

Biologist finds new approach to understanding the puzzle of human development

Imagine a line running down the middle of your body, dividing it into halves that, on the outside, mirror one another. But inside, this symmetry breaks down. Your heart sits to the left, accommodated by your slightly smaller left lung. Your spleen, part of your immune system, and stomach are to the left, while your liver is to the right.

This internal asymmetry arises early during embryonic development. Disruptions to it can have serious, even deadly consequences.

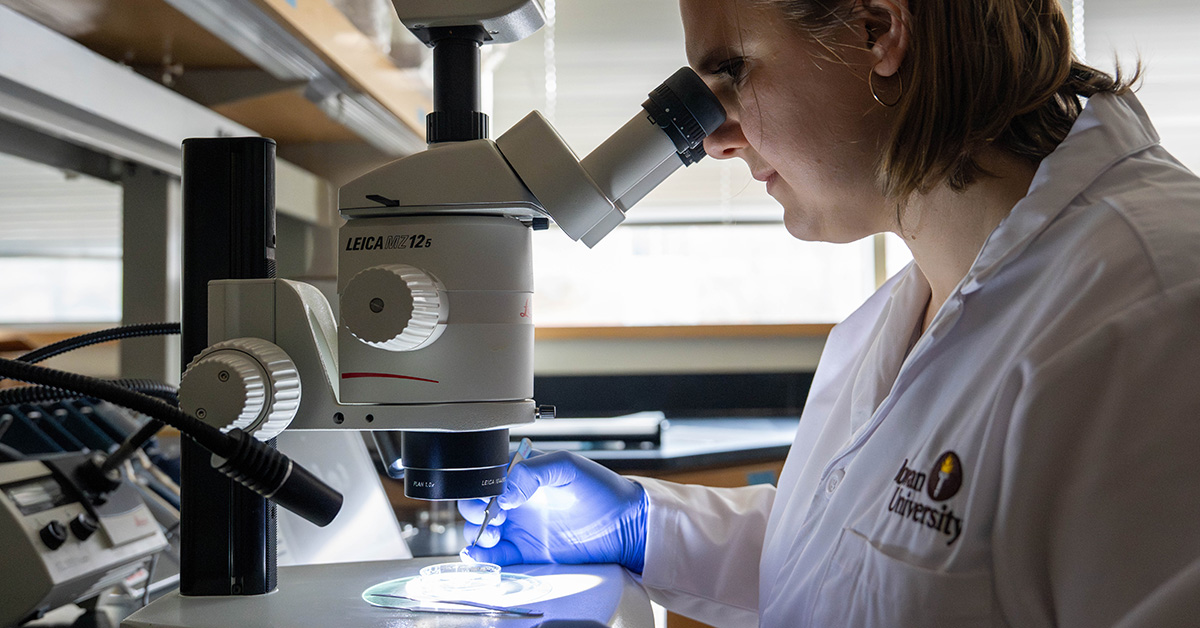

To understand how things might go wrong, Natasha Shylo, Ph.D., an assistant professor of biological and biomedical sciences in the College of Science & Mathematics, recently received a 3-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to explore left-right asymmetry development in animals. The grant, which provides nearly $744,000 in funding, builds on her previous work with veiled chameleons.

“In my postdoctoral research, I found that, in establishing left-right asymmetry, chameleon embryos do something very different from humans,” Shylo said. “It’s interesting in itself, but this difference also gives us the opportunity to study this developmental process from a new angle.”

For a brief period of early development, an embryo’s left and right sides are perfectly symmetrical. Then a temporary organ called the left-right organizer kicks off a process that will complicate the body plan. In humans, mice and some other animals, this organ possesses hair-like motile cilia that generate a leftward movement, followed by the release of calcium, which serves as a signal, on the embryo’s left side.

“People may assume left and right fall in place automatically, but that's not the case,” Shylo said.

Understanding congenital birth defects

Problems with left-right organization cause congenital birth defects, the leading cause of infant mortality in the United States, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The heart—which starts as a tube that loops asymmetrically—is particularly vulnerable. Infants born with these heart malformations often need surgery and frequently do not make it out of childhood. The spleen, intestines, liver, and other parts of the body may also be affected.

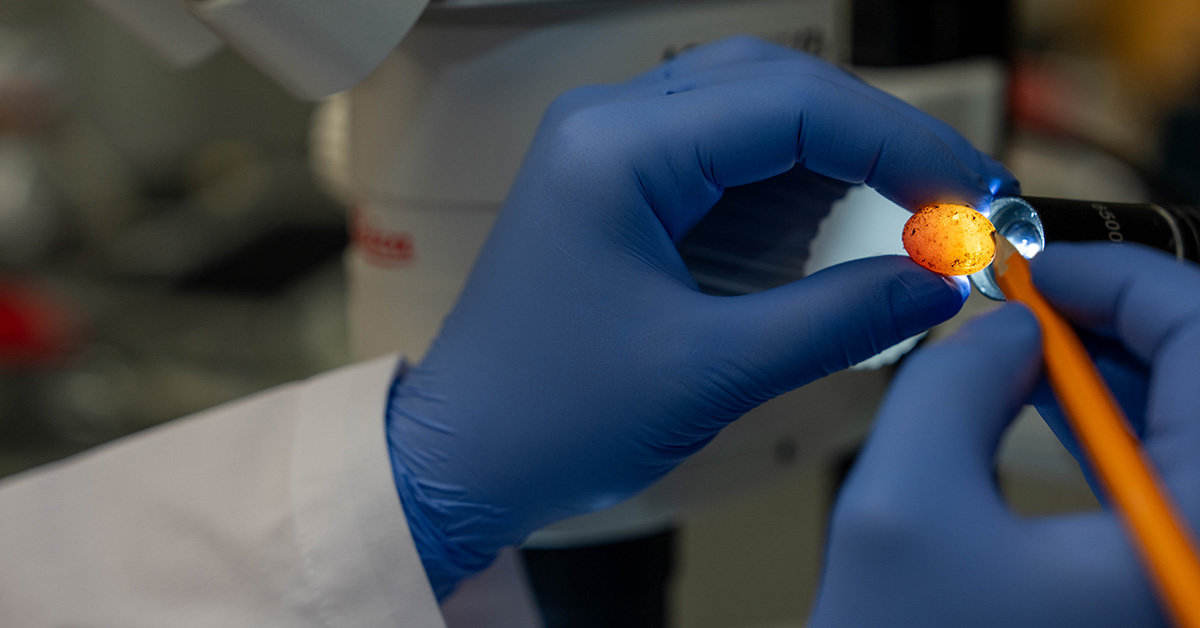

As a postdoc at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Shylo received NIH support for work leading to her discovery that chameleons lack the cilia credited with initiating left-right asymmetry in humans. Chameleons aren’t unique. Scientists think that the majority of four-limbed animals, including other reptiles, also lack these cilia.

“The big question is, well, how do they establish left-right asymmetry?” Shylo said.

Her current NIH grant, which kicked in when she joined Rowan’s faculty in September, is making it possible for her to look for an answer. She intends to compare processes she sees in chameleons with those in chickens, which also do not use hair-like cilia at this point in development.

While her research will shed light on how animals, including humans, position their organs, a more fundamental question remains: “Why does it matter if our heart and stomach are on the left and our liver is on the right?” she said. “We don't know.”

This research is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00HD114881. The content is solely the responsibility of the researchers and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.