Understanding the One Health approach and its impact on public health

Understanding the One Health approach and its impact on public health

Rowan Today writers sat down with Dr. John Ekakoro, assistant professor of epidemiology, public health, and food safety at Rowan University’s Shreiber School of Veterinary Medicine to get a better understanding of the One Health approach and its growing importance in addressing today’s most complex health challenges. As chair of Shreiber School’s One Health Research Cluster, Dr. Ekakoro shares his insights into the origins of One Health, its relevance to disease prevention and public health, and how Rowan University is uniquely positioned to advance this critical, interdisciplinary framework locally and globally

Beginning in Fall 2026, Shreiber School will offer a new Masters of Science in One Health program, designed for students pursuing careers in biomedical rsearch, public health, global health and health policy. Applications are available through April 15, 2026.

How would you explain the One Health approach?

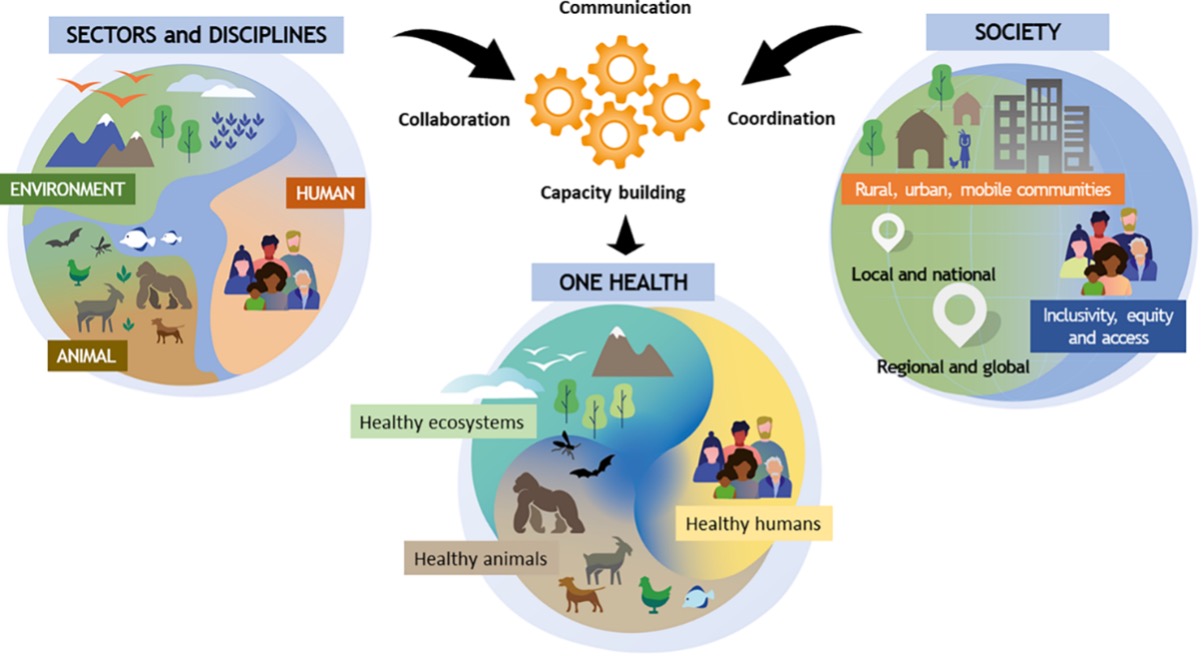

The One Health approach seeks to improve the well-being of humans, animals, and the environment by recognizing and optimizing the balance among all three. It is grounded in the understanding that human, animal, and environment health are deeply interconnected, and that each influences the other.

While the term “One Health” has gained traction in the recent years, the concept itself is not new. As far back as the early 1800s, pioneers in medicine viewed health holistically, with little distinction between human and veterinary medicine. Over time, these fields became more separated, but One Health represents a return to that integrated way of thinking, updated for the complexity of the modern world.

Why is the One Health approach so important?

Interconnected systems bring complexity, especially when responding to health crises such as disease outbreaks. In public health, we often talk about primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. When it comes to zoonotic diseases, those that spread from animals to humans, primary prevention is essential. That means preventing diseases in animal populations before it spills over into people.

Historically, outbreak responses tended to be siloed, with limited coordination across sectors. Today, professionals increasingly recognize that effective prevention and response require cooperation, coordination, and clear communication among experts in human, animal, and environmental health. One Health provides a framework for addressing these challenges holistically rather than in fragmented ways.

What risks arise when health responses are siloed?

Siloed approaches simply don’t address the full scope of the problem. If our goal is to protect public health, we cannot operate in isolation. Given the interconnectedness of life on our planet, diseases will move between animals, humans, and the environment, sometimes directly, and sometimes indirectly. Trying to keep these systems separate is neither realistic nor effective.

How do experts collaborate across veterinary, medical and environmental fields?

Collaboration across sectors has long been a challenge at local, national, and international levels. Differences in priorities, policies, and institutional frameworks can make working together difficult.

At the global level, organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) have developed frameworks to support and guide cross-sector collaborations. These efforts represent important steps toward more coordinated and effective responses to shared threats.

Are there misconceptions about the One Health approach?

Yes, there are a few misconceptions. One criticism is that because One Health addresses many interconnected issues, it lacks focus -- “if it’s about everything, then it’s about nothing”. One Health is about leveraging expertise from multiple sectors to solve clearly defined, high-impact societal problems. Life is complex and addressing complex challenges requires integrated solutions.

Take West Nile virus as an example. Public health professionals alone cannot control this disease without collaboration from animal health experts. It simply wouldn’t be possible.

Another misconception is that One Health is primarily a veterinary initiative or an attempt by veterinarians to expand their professional scope. While veterinarians play a critical role, many issues, such as foodborne illnesses like E. coli or Salmonella, cannot be effectively addressed by a single sector. These problems demand a coordinated, multi-pronged approach.

So, then what unique role do veterinarians play in this framework?

Veterinarians are uniquely positioned to advance One Health by serving as champions of both animal and public health. Many infectious diseases that affect humans originate in animals, making veterinarians essential to primary prevention efforts.

In many ways, veterinarians are the eyes and ears of public health. Their work in preventing and controlling diseases in domestic and wild animal populations, before those diseases spill over into human, is a cornerstone of effective One Health strategies.

Did the COVID-19 pandemic change awareness of One Health?

Yes, although the momentum began before COVID-19. For example, during the West Nile virus outbreak in the late 1990’s, the Wildlife Conservation Society recognized the need for a more integrated approach and convened the One World, One Health conference to raise awareness and chart a path forward for addressing zoonotic diseases.

The approach continued to gain traction, and in 2009, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established a dedicated One Health office. Even before COVID-19, the U.S. government had programs focused on predicting zoonotic disease outbreaks, and they anticipated that a global pandemic would eventually occur.

COVID-19 dramatically amplified public understanding of One Health. Outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 in mink farms and the detection of the virus in white-tailed deer underscore the importance of considering animal and environment health alongside human health.

Where do you see One Health research headed in the next decade?

I see continued growth and expansion of One Health research. At Shreiber School, we are actively investing in One Health research initiatives by providing seed funding to faculty engaged in this work. These investments are designed to support innovative proof-of-concept studies that will position researchers to successfully compete for larger, externally funded projects and expand the impact of their work locally, nationally and globally. We are also expanding opportunities for students through the Masters of Science in One Health program coming next fall.

Our One Health Research Cluster is engaged in critical research areas including food safety, antimicrobial use and resistance, PFAS or “forever chemicals” and the strategic use of animal diagnostic laboratory data to detect emerging and reemerging diseases. Together, this work addresses some of the most pressing and complex threats to public animal and environmental health and positions our research cluster to make meaningful contributions to global health security.

Rowan University is especially well positioned to advance One Health with Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, the Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine, the Shreiber School of Veterinary Medicine and strong undergraduate programs across environmental science and the humanities and social sciences. Rowan brings together a rate breadth of expertise under one umbrella. Few institutions are equipped with this level of interdisciplinary capacity to address complex One Health challenges.

What is the most important takeaway about One Health?

The key takeaway is that the health of humans, animals, and the environment is inseparable. Addressing today’s health challenges requires collaboration across the three domains. To truly protect public health, we must move beyond theory and fully operationalize One Health, for the benefit of all.

At Shreiber School, we are particularly eager to strengthen collaboration with the social sciences and humanities, an area widely recognized in the U.S. and globally as a major gap in One Health. Historians can help us understand how past events and societal patterns influence the emergence of disease outbreaks while writers and communicators play a critical role in translating scientific findings to the broader public. Without strong understanding of the social and human dimensions of health, even the most rigorous science-led initiatives risk falling short.

The above Q&A was written with assistance of AI using testimony given by Dr. John Ekakoro, assistant professor of epidemiology, public health, and food safety at Rowan University’s Shreiber School of Veterinary Medicine