The origins of swallowing difficulties in Parkinson’s

The origins of swallowing difficulties in Parkinson’s

Over time, the neurodegenerative disorder Parkinson’s disease robs patients of their ability to control their muscles, including those required to swallow food. Although not generally considered a major symptom of the disease, difficulty moving a meal from the mouth to the throat puts patients’ lives at risk, both from choking and from infections that develop from inhaling food into the lungs.

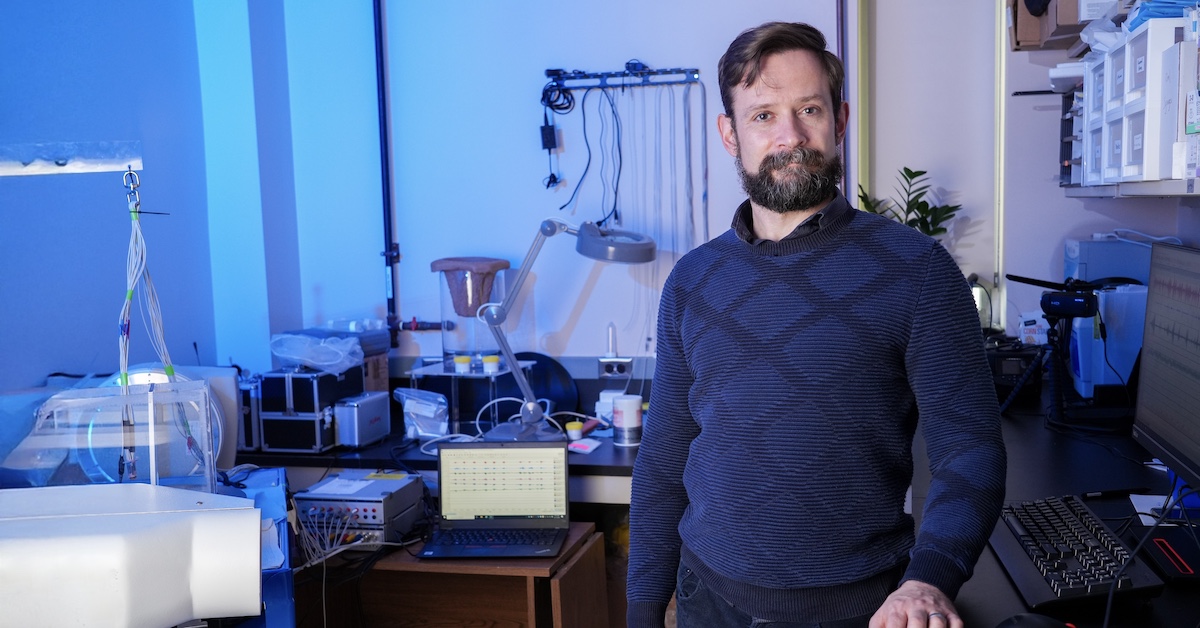

“We have drugs that improve the loss of control of limb movements in Parkinson’s, but the problem is they have no impact on swallowing dysfunction,” says François Gould, an assistant professor in Rowan-Virtua School of Osteopathic Medicine’s Department of Cell Biology & Neuroscience, part of Virtua Health College of Medicine & Life Sciences. “The drugs that fix one, don't fix the other.”

Gould has received a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to look for an explanation. Results from this project could help scientists better understand the scope and progression of damage within the brain and perhaps guide the development of therapies that specifically treat difficulty swallowing.

In Parkinson’s, one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders, neurons that make the chemical signal dopamine die off. This damage starts within a brain region known as the substantia nigra—which is essential for controlling the body’s movements—and spreads as the disease progresses.

The loss of dopamine leads to symptoms that include the movement-related problems—such as tremors, stiffness and slowness—most often associated with the disease. Although swallowing requires at least 25 sets of muscles and six nerves to orchestrate, difficulties with it are not typically thought of as a movement, or motor, problem, according to Gould. Beyond the immediate risk of choking, problems with swallowing can cause patients to inhale food. Over time, this can lead to pneumonia, one of the primary causes of death among Parkinson’s patients.

Difficulty swallowing accompanies many other conditions as well. These problems originate in the less-than-ideal anatomy of the human throat, which requires food to pass over the trachea, or breathing tube, to reach the esophagus on its way to the stomach.

“It's a cobbled-together system,” says Gould, a former paleontologist who studied the evolution of mammals. “We have inherited it from animals that didn't have to worry about breathing as much as we do; that’s what it boils down to.”

Current Parkinson’s medications, most notably the drug levodopa, increase dopamine and slow the worsening of motor symptoms. They do not, however, reduce deterioration in swallowing ability. Gould suspects this is because a different neurological mechanism, one distinct from the loss of dopamine production in the substantia nigra, causes swallowing problems.

The NIH grant will support experiments in his lab testing this hypothesis. Using a translational model, his team will simulate the early phase of the disease, before it is typically diagnosed in patients.

They plan to compare these initial neurological changes to those that occur later in the disease. Separately, they intend to look at the effects of Parkinson’s-like damage in brain regions beyond the substantia nigra to see if changes in these areas impair swallowing, and how. In both cases, they will record the electrical activity in muscles to see how signals from the brain change.

This research could identify specific mechanisms that become disrupted in Parkinson’s, pointing the way to new therapies that improve swallowing, according to Gould.

“We need to start thinking about Parkinson’s less-recognized symptoms, the neurodegenerative processes behind them, and what we can do to address them,” he says.