Reverent remembrance: Conference on Holocaust memorial books brings international scholars to Rowan

Reverent remembrance: Conference on Holocaust memorial books brings international scholars to Rowan

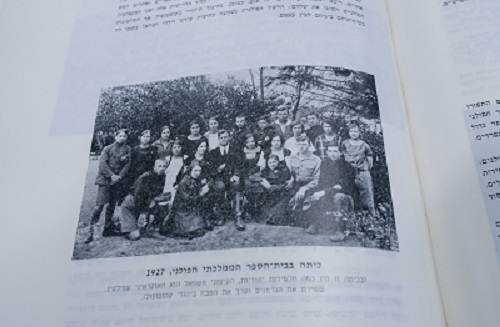

A black and white photograph appears on page 123 of “Sefer Kostopol,” a bound volume chronicling a small town in Ukraine.

Dated 1927, the photo depicts a class at a Polish state school. Children—Ukrainians and Jews—are casually dressed. They lean into one another, as friends do.

“Except in this photograph,” Rowan University Sociologist Jenny Rich said, “there is a murderer.”

The individual at the far left of the photograph is identified in the book’s caption as “the Ukrainian Shpilkin, who served the Germans and carried out the massacre of Kostopol Jews.”

The individual at the far left of the photograph is identified in the book’s caption as “the Ukrainian Shpilkin, who served the Germans and carried out the massacre of Kostopol Jews.”

“There is nothing violent in the photo, no sign of what was ahead for the young people who posed together one day in 1927, 14 years before the Germans occupied Kostopol,” Rich, executive director of the Rowan Center for the Study of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights and chair of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology in the College of Humanities & Social Sciences said of the photo (above).

“Instead, it shows how personal the betrayal and violence of the Holocaust was, how exceptionally ordinary the perpetrators could be.”

During the Holocaust, six million Jews were murdered and thousands of communities in Eastern Europe were destroyed. More than 1,000 bound books, including “Sefer Kostopol,” were painstakingly created by survivors to memorialize both the victims and their communities.

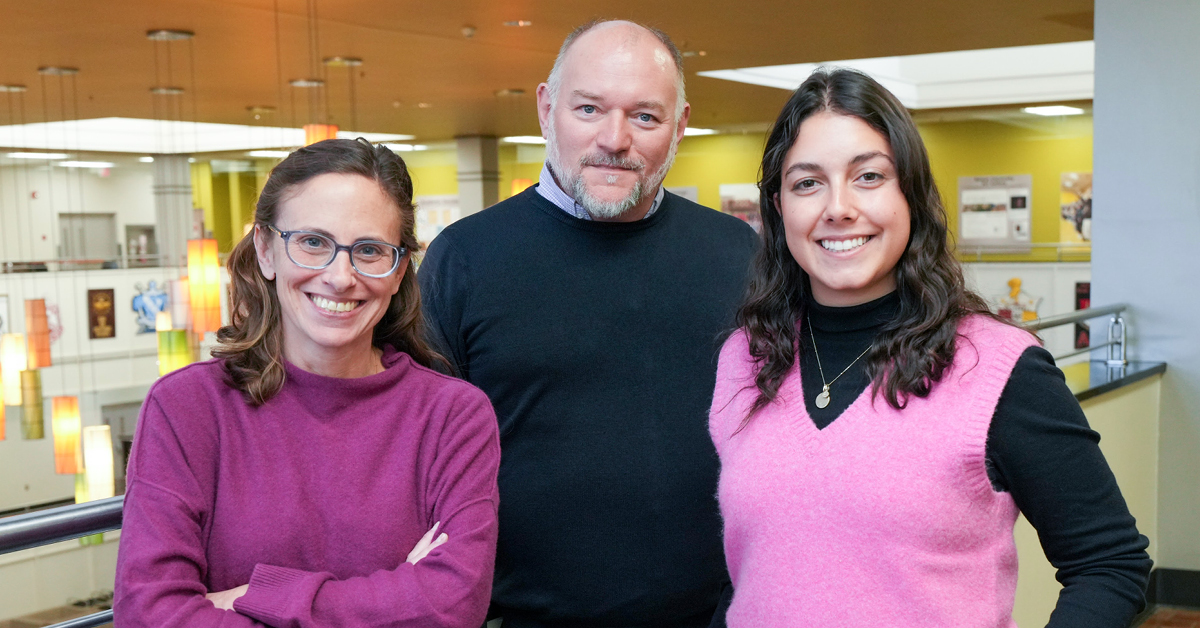

Last month, Rich and Robert M. Ehrenreich, a scholar at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, co-convened a conference at Rowan focused exclusively on the memorial books—known as yizker bikher.

International scholars joined together to engage in rigorous discussion on the power, legacy and historical and academic relevance of the books before an audience of community members and faculty and students.

‘Portable containers of memory’

Yizker bikher are “exceptionally under studied,” according to Rich, whose forthcoming book, “Paper Tombs,” focuses on yizker bikher. “Sefer Kostopol” tells the story of Rich’s grandmother’s Ukrainian community.

Communally authored and professionally printed, the books, similar in some ways to scrapbooks, include text, hand drawn maps, sketches, and photographs that document the daily lives of communities before the devastation of the Holocaust. The books also document the individual and communal experiences of violence during the Nazi era.

“They are comprised of everyday life before the Second World War: institutions, folklore, mythology, idioms, memoirs, biographies, and—only toward the very end of any given volume—individual and communal experiences during the Nazi genocide,” said Rich, whose grandmother survived the Holocaust.

Designed as “portable containers of memory,” Rich said, yizker bikher serve “as a perpetual global reminder of the Holocaust. Contributors actively sought to give readers, especially of those who never lived in Europe, a sense of the destroyed world.”

Almost exclusively, the word sefer, Hebrew for “book,” is included in the titles of all volumes. The use of the word implies a holy book—a sacred text, according to Rich.

“About two-thirds of any given book is about pre-war Jewish life, but this life is seen through the lens of its destruction. It is clear that contributors wanted to be remembered for the way they lived and not only for the way so many of their loved ones died. These books were a way for Jews to tell their own stories,” Rich said.

Everyday life

To that end, images in the books often are of school groups, sports teams, families, children, homes, community landmarks.

The majority of the photos are portraits, according to Steven Samols, the Rothschild Hanadiv Europe Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies at University College London.

“The shots are beautifully and well composed,” said Samols, an expert in Jewish topography. “There were a lot of skilled Jewish photographers across Europe. This is something particular to the Jewish perspective. This doesn’t even exist in other parts of Europe.”

Written collectively, “almost universally, the editors are male,” noted Eliyana Adler, a history and Judaic studies professor at Binghamton University. “Iterations of Belchatow,” a yizker bikher published in 1948 memorializing a Polish community, contained 23 essays by male authors, Adler said.

One of the most prolific contributors to yizker bikher was Nachman Blumenthal, according to Martina Ravagnan, collections manager at The Wiener Holocaust Library in London. The library is one of the world’s leading and most extensive archives on the Holocaust, the Nazi era and genocide.

A scholar, historian and Holocaust survivor who testified in war crimes trials against Nazi perpetrators in Poland, Blumental contributed to 20 distinct volumes. His wife, son and most of his siblings were murdered during the Holocaust.

“Blumenthal described yizker bikher as an emotional narrative,” Ravagnan said. “He was a real participant in the pain and sorrow.”

‘Vehicles of community’

Maps included in the books were drawn and labeled from memory by survivors, Rich said.

The map in “Sefer Kostopol” shows the fire station, factories, mills, markets, five schools, a soccer field, three synagogues and two churches. A ghetto—not formed until 1941—was included, surrounded in illustrations by fencing or barbed wire.

“Maps are, most importantly, vehicles of community,” said Aleksandra “Ola” Szczepa, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Potsdam. “Not every book contains a map, but most of them do.”

Yizker bikher are predominately written in Yiddish or Hebrew, according to Ehrenreich, the director of academic research and dissemination at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Museum. Six hundred books have been digitized and a third of them have been translated from Polish.

The New York Public Library has one of the largest collections of yizker bikher and Jewish Gen, a nonprofit genealogical society, has translated some of the books. Books are even available on Amazon, he said.

“People have a real connection to them,” Ehrenreich said, adding that the books have an “imbued sacredness.

“To a large extent, people haven’t really studied them. It’s amazing how complex they are. The language in them is important, but the materiality is equally important,” he added.

‘Let us hold them dear in our memory’

The volumes are thick and heavy, noted Ehrenreich and Emily Klein, program coordinator for the Broadening Academia Initiative at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“The books are not something you take lightly. A book’s heft enhances its gravitas,” Ehrenreich said.

Most of the yizker bikher conclude with necrologies—lists of the dead.

“A tombstone of paper must be erected,” one author wrote. “We, the survivors have to erect a sanctuary of paper to consecrate their souls.”

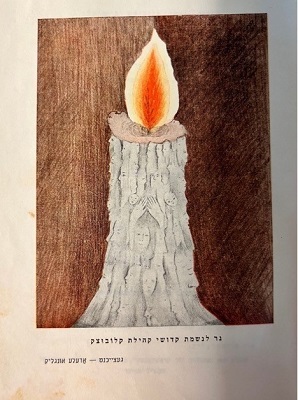

That’s apparent in “Sefer Klobutsk,” a memorial book about Klobutsk, Poland.

That’s apparent in “Sefer Klobutsk,” a memorial book about Klobutsk, Poland.

The book’s cover page (at left) includes an illustration of a single lit candle. The candle’s wax is made up of faces—“simple line drawings with little detail that represent the families—children, parents and grandchildren—murdered during the Holocaust,” Rich said.

The writing in yizker bikher is poignant and sacred, scholars agreed.

In an essay, Holocaust survivor Saul Zalud, writes about Kalisz, Poland, his hometown. Zalud gives his readers an account of the sights, sounds and smells of Kalisz—from the old market square to Maikow Field to the Prosna River.

His prose then ends abruptly.

“The city stands with all its beauty and charm, but the Jews are no longer there. Their birthplace has betrayed them. It has forgotten them,” he writes.

“But we remember. Let us hold them dear in our memory.”