Facing history: In 2022, remains of Hessian soldiers were discovered at Red Bank Battlefield. Today, experts strive to learn more about their humanity.

Facing history: In 2022, remains of Hessian soldiers were discovered at Red Bank Battlefield. Today, experts strive to learn more about their humanity.

Two years after the surprising discovery of the remains of 15 Hessians buried at Gloucester County’s Red Bank Battlefield Park, a New Jersey State Police sketch has given a human face to one of the soldiers killed in the landmark 1777 Revolutionary War battle.

Meanwhile, led by Rowan University Public Historian Jen Janofsky and history adjunct Wade Catts, a national team that includes forensic anthropologists and bioarchaeologists, historians and experts in DNA and stable isotope analysis is working to learn more about the soldiers who gave their lives fighting for the British crown against outnumbered-but-emboldened Patriot forces.

Moreover, a Clarksboro couple has given a financial gift to support research that they hope could possibly ultimately help identify one or more of the soldiers. And Rowan students have been intimately involved in both telling the story of the Hessian soldiers and in documenting the project through digital photography.

“A diverse group of people have committed their time, energy and expertise to moving this project forward,” says Janofsky, director of Red Bank Battlefield Park. “The search for someone’s identity, lost to history, touches something deep in the human experience.

“As a public historian, I want to complicate people’s understanding of ‘the enemy.’ I want the public to have a deeper connection to the battlefield. I want them to experience historical empathy. I want them to see these remains as human beings. Our project has done just that.”

In the time since a member of the public—a union electrician—discovered part of a femur during a public dig day in June of 2022 organized to uncover material culture at Red Bank, here are some of the developments in the story:

A human face

A cone-shaped headdress perches on his head. His hair peeks out from underneath, falling to the nape of his neck. His gaze is transfixed, seemingly focused on duty. His posture is perfect, his mustache thick. Even in full military regalia, he looks like a young man.

A cone-shaped headdress perches on his head. His hair peeks out from underneath, falling to the nape of his neck. His gaze is transfixed, seemingly focused on duty. His posture is perfect, his mustache thick. Even in full military regalia, he looks like a young man.

His is the face of one of the Hessian soldiers killed at Red Bank.

“It gives me chills,” Janofsky says of the composite sketch (at left) of one of the soldiers prepared by artist Moises Martinez of the New Jersey State Police Forensic Technology Center.

Working from a skull that was among the remains discovered at Red Bank, Martinez created the sketch to give a human visage to one of the soldiers. The skull was one of two complete crania recovered in the Fort Mercer trench at Red Bank.

The sketch is part of an exhibit at Red Bank’s Whitall House. The exhibit contains objects found in digs at the battlefield since 2022.

Clues from bone fragments and teeth

Utica University Forensic Bioarcheologist Thomas Crist, working in concert with State Police Forensic Archaeologists Anna Delaney and Stuart Alexander, examined the recovered bone fragments and teeth to determine age and gender.

Their research found that the soldiers were fairly robust white men of European descent, all young to middle-aged adults. There were no teenagers, according to Crist.

Seeking DNA markers from the petrous bone

Initial testing by Astrea Forensics in California, a forensic genome sequencing service laboratory, also confirmed the samples of the remains are male. But additional information could not be gleaned due to the poor condition of the remains, which were degraded from sitting in wet soil for nearly 250 years.

However, studies on a specific area of two recovered skulls could possibly give researchers another avenue to recover additional DNA markers.

Through her Historical Genomics Lab, Dartmouth College Anthropologist Raquel Fleskes, an ancient DNA specialist, has joined the team to test DNA from two petrous bones. Located inside the temporal bone, the petrous is the hardest bone in the body and tends to contain well-preserved DNA.

Fleskes, whose lab focuses on understanding the population histories in early colonial North America, works with Historic Jamestown and Colonial Williamsburg.

Supporting additional studies through stable isotope analysis

Researchers from the University of Georgia also will conduct stable isotope analysis on the teeth.

Isotopes are chemical signatures preserved in bones and teeth that remain uncompromised over time. Stable isotope analysis will give researchers information about the soldiers’ diet and, also, population movements, which will provide valuable background on them.

“Over the past two years, I’ve come to appreciate the complexity of research required to identify remains,” says Janofsky, the Megan Giordano Fellow in Public History in the College of Humanities & Social Sciences.

“DNA analysis and stable isotope testing hold the potential to identify our soldiers. We will exhaust all resources to try to recover the stories of these men.”

The possibility that one or more of the soldiers could be identified inspired county residents Bob and Martha Gilliam to give the first private gift to the project. The Gilliams, who gave $20,000 to fund the stable isotope analysis, have a keen interest in learning more about the Hessian soldiers who gave their lives on foreign soil and whose remains were unceremoniously dumped in a battlefield ditch.

“To the extent that it is scientifically possible, we want to support an effort to definitively identify one or more of the Hessian soldiers buried at Red Bank,” says Bob, chairman of the Woodbury-based Vanguard Adjusters Group Inc. and a 1988 Rowan alumnus. Martha is the company’s executive vice president of finance.

“The idea that we could someday take a trip to Germany and knock on the door of a descendant is just amazing,” he continues. “There’s a story here everyone can learn from.

“This is an opportunity for us to get the recognition Red Bank deserves as a pivotal moment in America’s history.”

Researching Hessian history

On Oct. 22, 1777, Patriot forces prevailed in the Battle of Red Bank, which Janofsky calls “the greatest upset of the American Revolution.”

Some 2,000 soldiers strong, the Hessians suffered heavy casualties—approximately 377. The Americans, integrated regiments of Black and white soldiers fighting for freedom side by side, numbered 500. Fourteen Americans were killed. The battle was a key defense for Americans to delay the British from advancing supplies up the Delaware River to Philadelphia.

Project historian Robert Selig is meticulously researching Hessian historical records to try to uncover the identities of the soldiers.

Both the von Mirbach battalion and the von Minnigerode battalion of grenadiers took heavy casualties in the area where the remains were discovered, according to Selig.

Using primary military sources and primary civilian sources, including HETRINA (Hessian Troops in the American Revolution), Selig has focused primarily thus far on von Mirbach. According to Selig, few of the rank-and-file soldiers killed in action from that regiment are accounted for in HETRINA. The documents list mostly Hessian officers that were killed. Unlike other areas of Germany, newspapers in Hessen at that time did not contain records or lists of casualties.

Selig’s research shows that soldiers in the regiment came from more than 90 different communities. The Battle of Red Bank was the only combat action the von Mirbach battalion saw in the war.

Involvement by Rowan students

At the New Jersey State Police Forensic Technology Center in the spring, Janofsky and Brendan Coulthurst peered into a tray filled with dust-covered and fragile sections of jaws, skulls and arms.

“This,” Janofsky said quietly, “is what a battlefield looks like at the end of the day.”

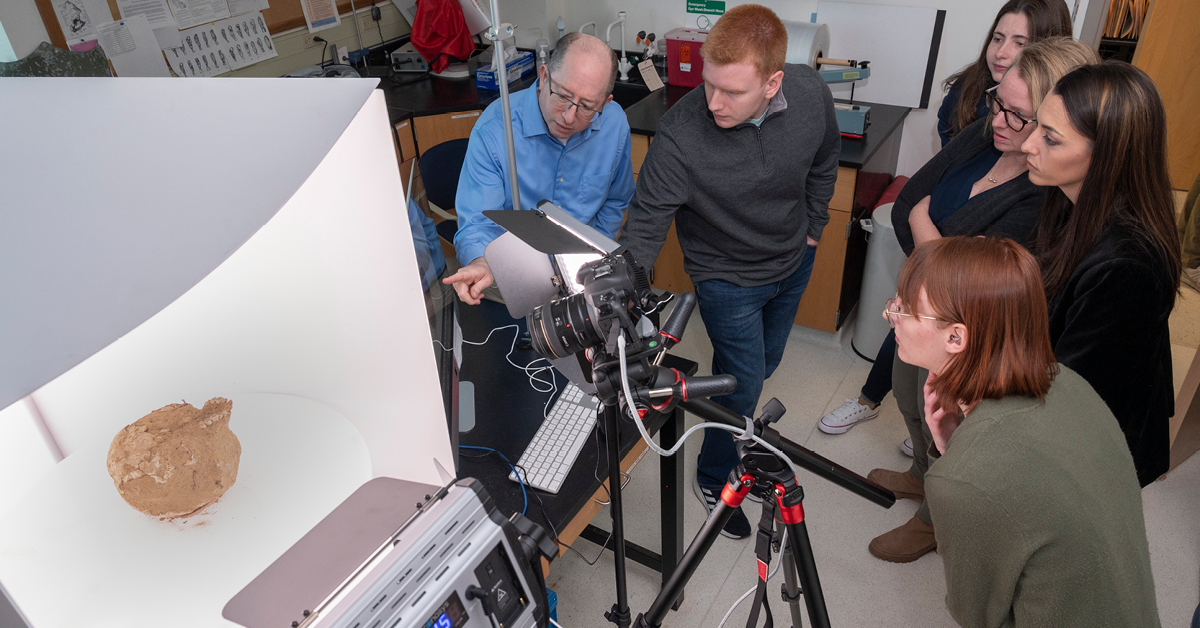

Coulthurst, a history and anthropology major, felt the enormity of the work as he and fellow student Annabelle Sebastian, an anthropology major, painstakingly, reverently took 360-degee photos of the remains to document the project.

The students completed the photography of the remains and recovered historical artifacts for Rowan Libraries’ Digital Scholarship Center.

“You start to feel connected to them,” Coulthurst said. “You’re literally seeing them in a different light. It’s very emotional.”

Other Rowan students have been involved in telling the Red Bank story through internships at the park and through Field School courses the past two summers.

A historical and recreational treasure in Gloucester County

Owned and maintained by Gloucester County, the 44-acre battlefield site sits on a bluff above the Delaware River in National Park. In 2020, the county secured a land preservation grant to purchase a quarter-acre lot that contains part of the Fort Mercer trench.

A $19,000 New Jersey Historical Commission project grant in 2021 funded an initial archaeology survey on the parcel, as well as a public education and outreach program. The county committed $30,000 in additional funding for the second phase of the project.

“Red Bank Battlefield Park is one of Gloucester County’s historical and recreational treasures,” says Director of Gloucester County Board of Commissioners Frank J. DiMarco. “We’re proud to continue to support the public archaeological work that highlights Red Bank’s importance in Revolutionary War history.”

Public interest continues to grow

Since the announcement of the discovery of the remains, which garnered international attention, interest in Red Bank has increased dramatically. Since 2022, nearly 400 community members have participated in public dig days. Moreover, Janofsky and Catts, principal archaeologist for South River Heritage Consulting, have given more than 20 public presentations.

August tours of the discovery site

Park volunteers, including Rowan students, will give guided, registration-only tours of the Hessian discovery site on three Saturdays in August—the 10th, 17th and 24th. Registration is online. Visitors must create an account and click the “activities” tab to go to the registration site.