19th century writings of Black activist come alive during Rowan transcribe-a-thon

19th century writings of Black activist come alive during Rowan transcribe-a-thon

The 19th century penmanship was a challenge.

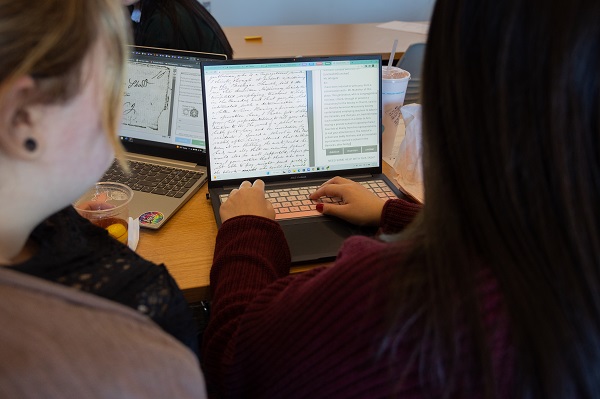

But Kayla Maharaj and Amanda Beckman plowed through, word by word and, sometimes, letter by letter.

Together, the two senior history and education majors helped transcribe a personal letter of Mary Ann Shadd Cary, a Black journalist, writer and activist, during Rowan University’s first-ever Douglass Day Transcribe-A-Thon, hosted by the College of Humanities & Social Sciences.

The digital humanities event brought together nearly 100 people—students, faculty and community members—to transcribe writings by Shadd Cary. Laptops at the ready, participants accessed online archives of Shadd Cary’s letters, newspaper articles and other documents and transcribed them as part of a daylong observation of Douglass Day.

Coordinated by the Center for Black Digital Research at Penn State University, the crowdsourcing event, held on what is recognized as the birthday of abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass, included more than 7,000 participants across the nation who worked together to transcribe the writings of Shadd Cary, considered by some scholars to be an unsung hero of 19th century activism.

Participants accessed an online database of Shadd Cary’s work to transcribe the documents, contributing to efforts to help historians and the public learn more about her and, in turn, more about Black history. The collection of Shadd Cary’s papers was curated by Penn State.

Applying digital technology to the humanities

“The documents have been scanned and digitized, but not transcribed,” said Rowan historian Jessica Mack (below), who is teaching a new course in digital history at Rowan.

“The field of digital humanities is about applying digital technology to humanities research,” Mack continued. “This work is absolutely about accessibility. It’s focused on collaboration, community engagement and reaching out to the public. It’s very public-facing work.

“The field of digital humanities is about applying digital technology to humanities research,” Mack continued. “This work is absolutely about accessibility. It’s focused on collaboration, community engagement and reaching out to the public. It’s very public-facing work.

“The more primary source documents we make accessible, the more people can learn about Black history, women’s history and other histories that have been underrepresented. As students transcribe the documents, they are also reading closely and learning about these important stories.”

The transcribe-a-thon on Feb. 14 marked the first time that papers and records from Shadd Cary’s remarkable life have been gathered in one place. The first Black female publisher and editor in North America, Shadd Cary published “The Provincial Freeman,” a newspaper in Canada, in the 1850s. An abolitionist born to well-to-do free Black parents, Shadd Cary was “a trailblazer who contributed to Black intellectual tradition,” according to historian Chanelle Rose, coordinator of Africana Studies at Rowan.

Shadd Cary was born 200 years ago this year.

“She was a strong advocate of integration and believed integration was the best way to achieve freedom,” Rose said of Shadd Cary, who was one of the nation’s first Black female law students. “Black independence, self-respect and education are major themes of her work.”

The other Mr. Whipple

Maharaj and Beckman saw that firsthand as they worked together to transcribe a letter from Shadd Cary, written in Windsor, Ontario, to a Mr. Whipple.

Using 21st century technology to enlarge the letter, written in perfect, 19th century script, Maharaj and Beckman first conducted an internet search of Mr. Whipple, which identified him as a bathroom tissue huckster in 1970s advertising.

But a more detailed search using “Mr. Whipple” and “Shadd Cary” led to George Whipple, who was secretary of the American Missionary Association, the most significant society for Blacks during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Whipple worked to educate free southern Blacks.

“When I got Mr. Whipple and then looked it up, I saw the connection,” Maharaj said. “It was really cool.”

Maharaj and Beckman, two self-described “history nerds” and aspiring teachers, soon got accustomed to Shadd Cary’s penmanship and writing style, taking about a half-hour to pour through and transcribe the document. The letter even included cross-outs.

“They didn’t have erasers back then,” laughed Beckman, who acknowledged that she “speaks grandmom” because the penmanship is much like her grandmother’s.

“History is my thing,” Beckman added. “Reading the letters makes it more personal to me.”

Engaging primary source documents

Transcription of the documents enhances searchability and discoverability for scholars, promotes public access to documents, and encourages teachers to use primary sources in the classroom, according to Mack. The transcribe-a-thon encouraged broad participation, bringing history right to participants’ laptops.

Materials for the transcribe-a-thon came from libraries and archives. The largest collections are housed at the Archives of Ontario and the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, according to the Douglass Day web site.

Participants had the choice between transcribing hand-written letters, including some recently discovered in a trunk in a farmhouse, and printed materials, such as articles from Shadd Cary’s newspaper. After fact checking and verification, the work of the transcribers will go online and be available to scholars and the public, Mack said.

“As history professors, we love to see students engaging directly with primary source documents,” Mack said. “The students really like that the writings are online and accessible at their fingertips. One student said she felt she was helping to make history.”