NSF CAREER Award: Rowan researcher to study how gut microbes in honey bees influence social behavior

NSF CAREER Award: Rowan researcher to study how gut microbes in honey bees influence social behavior

Bees worldwide are in trouble, and with the future of agriculture and food production hanging in the balance, scientists are working hard to understand why entire colonies of honey bees are disappearing.

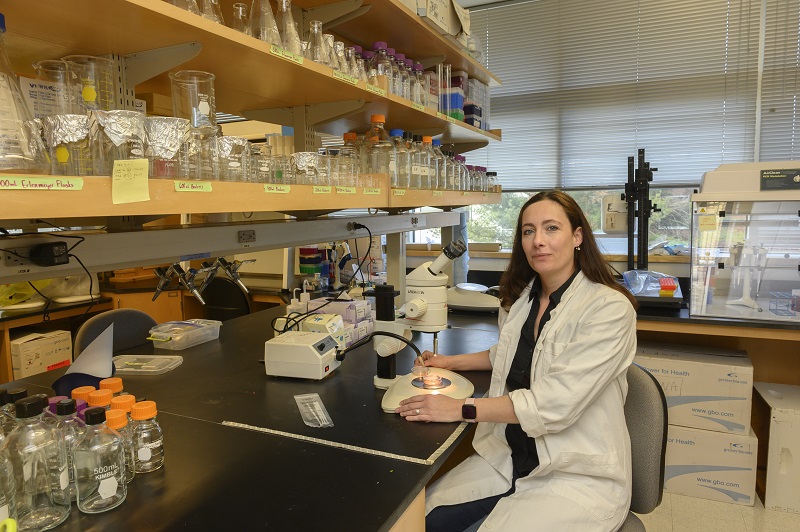

Now, with a National Science Foundation CAREER award totaling $763,600 over five years, Rowan University’s Dr. Svjetlana Vojvodic is launching exciting new research to examine how the bacteria in a bee’s gut might influence behavior. Understanding bee biology might shed light on colony collapse disorder, a leading contributor to the global disappearance of bees.

The work could help researchers understand the mechanisms behind microbial influences on human behavior, as well.

Awarded annually, the Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program offers the National Science Foundation’s most prestigious awards to support early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education.

Beena Sukumaran, Rowan University’s vice president for research, said this is the second CAREER award given to a Rowan University researcher this year, and only the fifth in the school’s history. The honor is an indicator that Rowan’s emphasis on scientific research is attracting faculty interested in exploring questions with global implications.

“They’re top notch,” Sukumaran said. “We’re drawing very high quality faculty that any institution would be happy to have.”

Nearly every spring since starting her research at Rowan University in 2014, Vojvodic has opened her bee boxes only to find a lonely queen and perhaps a few nurse bees. The worker bees fly out and never come back.

“There’s really no trace of them,” said Vojvodic, who grew up in a family of beekeepers in former Yugoslavia.

“Is it possible that pesticides or some kind of disease is changing the gut microbiome of bees, and that’s changing their behavior and leading to bee losses? It’s possible,” said Vojvodic, an assistant professor who teaches in the University’s Department of Biological Sciences.

“Let’s say the bee has encountered some kind of pesticides, and her learning is impaired. She cannot navigate back home, and she’s lost. That would be a potential link between the gut microbiome and bee disappearance.”

Honey bees are one of the most complex social organisms besides humans, she said, and they’re smart. Thousands of individuals live together, learning, communicating, and working as a community to find food, care for their young, and respond to diseases.

Vojvodic’s research indicates honey bees learn better if their guts contain a particular strain of bacteria. That’s a clear link that a bee’s microbiome — good bacteria in the gut — somehow contributes to memory or learning. The study will also examine bees’ social behavior, and explore which genes in their brains are tied to behavioral changes.

That research ties directly to the observed changes in the gut microbes of humans with certain disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder and Parkinson’s disease.

The research grant includes funding for undergraduate students to assist Vojvodic with the labor-intensive work, much of it only possible during the summer when bees are active. The grant will also enable Vojvodic to develop educational programming that can be used in local high schools to nurture student interest in science and research.