Considering chopsticks: Professor’s book documents historical, cultural significance of eating tools

Considering chopsticks: Professor’s book documents historical, cultural significance of eating tools

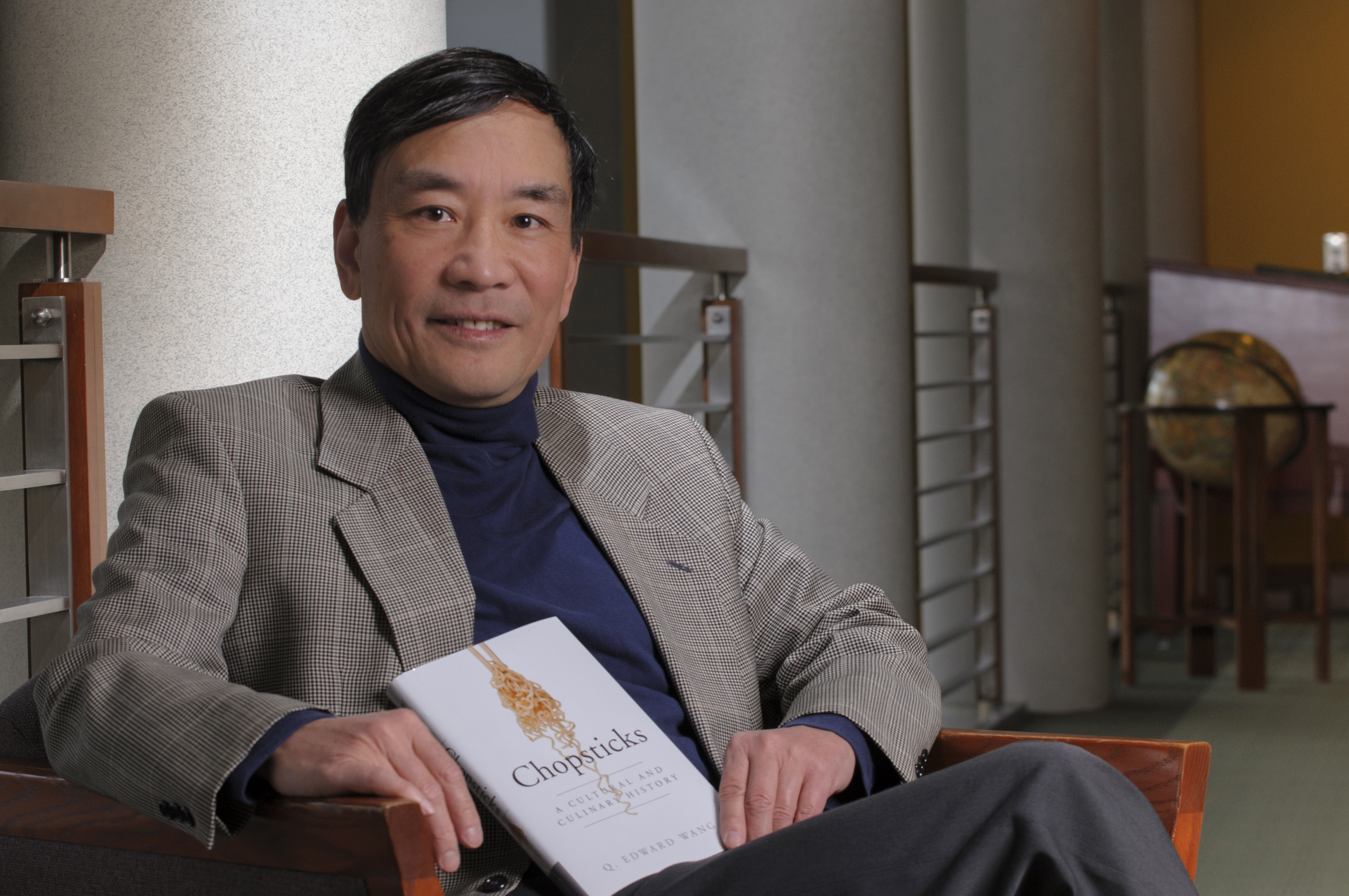

More than one-fifth of the world’s population uses chopsticks every day. But when Rowan University History Professor Q. Edward Wang sought to learn more about the history of the popular—and culturally significant—eating implements used by 1.6 billion people daily, he came up relatively empty.

“I really wanted to read a history of chopsticks. I found there’s no book in English. I read the Chinese and Japanese books. The Chinese did not look at things historically and the Japanese scholar had his own biases,” says Wang, a Rowan professor since 2001.

So Wang, who studies historiography—how history is written—decided to take a scholar’s approach as he delved into the vibrant, fascinating history of chopsticks. The result? Chopsticks: A Cultural and Culinary History, published this month by Cambridge University Press. It is the first book written in English on the topic.

Learn more about Wang’s book and research at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8vxaBC50NQ

In the works since 2010, Wang’s book charts the evolution of chopsticks from simple eating implements in ancient times to their status today as a more complex cultural symbol. Wang’s research shows that chopsticks were invented about 7,000 years ago, but were not always the primary eating tools in East and Southeast Asia.

Growth of wheat

Neolithic ruins in present day Gaoyou, Jiangsu, uncovered in 1993, date between 6600 and 5500 BCE and include 41 bone sticks believed to be chopsticks, according to Wang. But the spoon predates them, he says.

“The spoon was actually the earliest and most important eating implement for the people in ancient times,” says Wang, the author of several books on global and Chinese history.

Chopsticks gained popularity in the 1st Century as the appeal of wheat grew as a food, Wang says.

“The changing ways of food production and preparation exerted a major impact on the choice of utensils by their users. By the 10th century, wheat succeeded in dethroning millet as the most consumed grain among the northern Chinese, followed also by the Koreans,” Wang says. “Wheat flour foods, such as noodles and dumplings, combined grain and non-grain foods in one form. To eat noodles, chopsticks clearly were the better tool.”

From the 11th century, the increased consumption of rice in Asia also helped chopsticks gain popularity, according to Wang’s research. Interestingly, chopsticks use began in lower social classes and spread to upper classes. Today, the proper use of chopsticks is associated with good table manners, Wang says.

Elegance in eating

“To the Chinese and other Asians, using utensils to convey foods represents cultural advancement,” he explains. “The exclusive use of chopsticks as the eating tool, as well as the development of communal eating, probably began with the lower social classes in Chinese and other neighboring societies.

“The instrument was more readily adopted as the sole eating device by people of the lower social strata than those of the upper echelon. At the same time, chopsticks grained ground at the expense of other eating implements also because of the development of table manners and rudimentary concern for food cleanness and hygiene. In pre-modern times, using chopsticks was the most hygienic way to eat.”

In China, “two things show how your upbringing is: How you eat and your handwriting,” notes Wang, who grew up in Shanghai. “Using chopsticks properly displays elegance in eating. Eating food with chopsticks also will slow you down and help you enjoy your food more.”

‘Chopsticks cultural sphere’

Wang’s book outlines differences between people from China, the Korean Peninsula, the Japanese archipelago and parts of Mongolia and Southeast Asia. He calls the region the “chopsticks cultural sphere.”

According to Wang, the Chinese enjoy artistic, sometimes elaborate chopsticks. Disposable chopsticks were invented in Japan, which has one of the highest forestations in the world, Wang says.

“The Japanese don’t want to share chopsticks—or underwear,” Wang laughs. “They believe your spirit will attach to your chopsticks and it won’t be washed away. Also, Japanese chopsticks are shorter because they don’t share food. They use a bento box meal and the chopsticks need to fit inside. The Japanese have festive chopsticks for religious holidays.”

Koreans prefer flat or square metal chopsticks and combine them with a spoon while eating, according to Wang.

‘A symbol for life’

And while different cultures have adapted chopsticks for their own use, the eating tools are, across the board, culturally significant, Wang notes. Poetry, fairy tales, folk tales and fables have written about them. Chopsticks are frequent wedding gifts because they symbolize oneness. And, for the Japanese and other Asians, the utensils are a symbol for life, according to Wang.

It’s not surprising, Wang says, that there has been no instruction book on the proper use of chopsticks. Asians, including Wang himself, learn proper etiquette from the parents, a tradition that is passed on from generation to generation.

“Among users, chopsticks have been interwoven, naturally and seamlessly, into the basic fabric of daily lives. Chopsticks and their use have become a living tradition,” says Wang, who is co-coordinator of Asian Studies at Rowan and also serves as the Changjiang Professor of History at Peking University in China.

Wang will sign copies of Chopsticks on Wednesday, Feb. 25, at 11 a.m. at the Barnes & Noble Collegiate Superstore on Rowan Boulevard.